This originally appeared in The Independent on Sunday last year, on the 50th anniversary of the death of Ernest Hemingway, and the 320th anniversary of the Pamplona bull-run (in its modern form). It is extracted from the Sports Book Of The Year 2011 shortlisted Into The Arena: The World Of The Spanish Bullfight (available from as from Amazon US here and Amazon UK here, as paperback, eBook or audiobook.)

When I arrive in Pamplona it is at the height of what seems to be a Rio carnival-style street party, although, strikingly, everyone is in the same uniform – white shirt, white trousers, red neckerchief and red sash. These bull-running festivals used to be far more common, and there are still a fair few in Spain. They also happen across the border in France, in towns like Dax and Bayonne. They even happened in England until the mid-nineteenth century. The most famous one was in Stamford, Lincolnshire until it was banned in 1839 by the RSPCA.

Of all bull-runs in the world, though, Pamplona is the most famous, and for one reason alone, the writings of Ernest ‘Papa’ Hemingway. This even though it is generally accepted that he never actually ran. By generally accepted I mean by everyone except Hemingway himself. While researching this I came across a front-page story in the Toronto Daily Star in 1924, with the wonderfully self-referential headline ‘Bull Gores Toronto Writer in Annual Pamplona Festival’.

(I asked his grandson, the writer John Hemingway, about this and got the following pithy response: ‘Well, excuse the pun but I think that there was a lot of bull in my grandfather’s dispatches to Toronto in the ’20s.’)

First of all I walk out the ground of the run. It is a half-mile of streets with three corners, all of which are now packed with drunken revellers. I ignore them, trying to see how I am going to deal with the next morning, looking at the height of the bars on the windows and the height of the heavy wooden barriers, like a climber looking for a route of ascent or a burglar looking for a point of entry. I see some likely spots, but I have no idea as yet how the crowds will be in the morning.

I get to bed at about half past twelve – the run is at 8 a.m. – but I do not fall sleep until three in the morning.

Three hours later I wake up just before my alarm. I shower and slowly dress in a carefully selected version of the traditional dress for the day. A white cotton shirt and white denim trouser – nothing that inhibits movement, but tight enough not to be caught on a horn unless I am, and thick enough that protection against minor slashes is given. I tie the red bandana around my neck, mimicking the blood of the martyred Saint Fermín, in whose honour this festival is, and tie the red sash around my waist, wrapping it twice so there is no slack to catch.

At the entrance to the Town Hall square section of the run there are hundreds upon hundreds of people milling, moving, edging from foot to foot and emitting a combined stench of urine, alcohol and vomit that is nearly overwhelming. The one thing they do not stink of is fear. Fear itself has no smell, despite what the novelists say.

I find my spot in the street with an hour to go and overhear an Australian man say to his sylph-like girlfriend, ‘I’ll look after you.’ The astonishing naïvety of the remark annoys me. What is he going to do? Pick her up and throw her over the people stacked four deep and the six-foot fence behind them? While running? Because anything else he tries with a 1,400lb Miura running at thirty miles an hour won’t nudge it even one degree off course. If he wants to save his seven-stone girlfriend, who won’t stand a chance of dictating her own trajectory among panicked twelve-stone men, he should get her out now, and if he’s stupid enough to talk like that he should probably follow suit himself.

I decide to get away from them, ducking under the fence and heading away from the course to a small church where I had been told me the hardened runners gather – some Spanish, some Americans who have been doing it for as many as thirty years. In this little enclave of calm, I watch the men greet each other briefly with cordial handshakes and short sentences, confident and focused, not indulging in nervous small-talk, each parting with the word ‘suerte’, ‘good luck’. Their confidence is contagious.

I run a little and stretch like I used to fifteen years ago in my school athletics team and begin slaloming between traffic bollards at a half-sprint. By half past I’m dripping with sweat and adrenaline and as ready as I will ever be. Am I nervous? No. Not now. It is beyond the time for that. There had been moments during the sleepless night before when I thought, given that no one knows me here, I could say I had done it without doing it at all. Or I could not do it and no one would judge. At least not in any way I would care about. But in that odd way the mind has, having committed to a course of action, I will go through unless I can find a justifiable way out. And for this one I can’t. It’s Pamplona after all. I walk down the hill and take my place and wait.

As the time approaches, the streets thicken with people, then seem to clear. I later discover that this is an artificial density, as the final section of the run is closed until ten minutes to eight. I find myself alone in a section of street that has a crowd on steps behind the barrier watching like an audience. I find it very odd to be walking on what feels like a stage at a time like this. With five minutes to go that feeling fades. That is when the false breaks begin: all of a sudden a group of people will get the jitters and run up the hill, convincing other people – ones with untrustworthy watches or untrusting minds – that the bulls have been released early. I have no idea if they leave the course or decide to stay further up, but they don’t return to my space, my little island.

The minutes pass slowly. Incredibly slowly. I can safely say that no period of time in my life has ever passed that slowly. This is firing-squad stuff. The background noise and movement of the runners escalates, so that when the clock tower bells chime the hour I do not hear them. However, I know my watch is good so I am not exactly surprised when a rocket explodes in the air. I am certainly fully awake though.

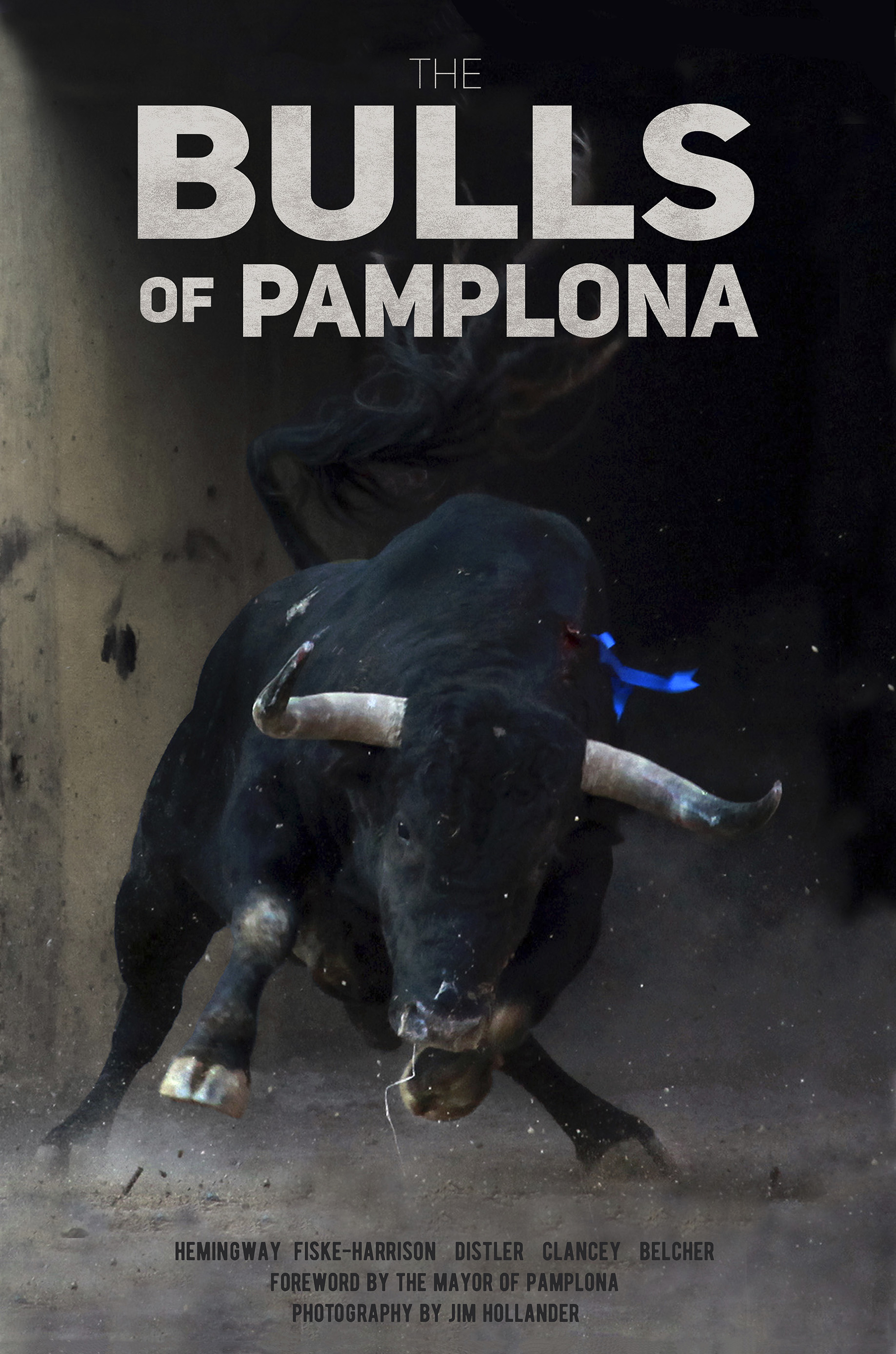

Then come the joggers, people laughing off their fear and embarrassment, but having made the very clear decision that they want to be further away from whatever is about to happen. When the second rocket goes off a few seconds later, they accelerate and I have to turn sideways to let the rush past. Then I bend my knees a little and lean my shoulder downhill, forcing people to part round me because this is becoming a stampede. And then the bulls turn the corner at the bottom of the hill and the thin blue line of police holding the people and the bulls apart breaks off to the sides and the mass of people shatters and flees like a medieval rabble under a heavy cavalry charge.

* * *

Of the many things I have seen researching this book, again and again the phrase ‘never seen before’ springs to my typing fingers, but this really was a sight that very few people in the modern era will see: a populace put to flight through its own streets, as though a siege has been broken, a city wall breached. As the bulls cleared their path up the hill and I attempted to hold my ground, people were running past screaming, grabbing at me, diving against the wall, which was now thick with people trying to make sure they were not the front line. As the bulls got closer – it seemed like ten feet away, but I would calculate from the images I have seen it was twenty – a clearer space in front of them enveloped me and I turned and started to run.

When I was in the athletics team at school, I had it drilled into me that you can think you are sprinting flat out, but then you look inside yourself and find an extra reserve of speed. However, this was not one of those times. I had enough adrenaline in me that I don’t doubt for a second that I have never run faster and that if I hadn’t warmed up I would have done a lot more than ended up with a strained Achilles tendon and aching hamstrings.

However, the bulls were much, much faster. By the top of the hill – maybe fifteen yards away – the front ones were passing me, the relatively harmless but massive steers between the bulls and me, but then I spotted one fighting bull, chewing his way through the people to my rear, his horn visible behind the falling man behind me. [A photo of this the masthead image of this blog. Ed.]

As he neared me, and the mass of people in the square began to push me and themselves towards his horns, I decided enough was enough and pushed myself back into the crowd on the side. The Miuras had passed, but I was not finished.

I jumped back into the middle of the street and went back to sprinting in an attempt to follow them, out of the town square, along calle Mercaderes and into one of the most dangerous parts of the course, the corner of calle Estafeta. As I reached it I was confronted with the sight of a fallen grey and white Miura, a suelto, a ‘loose one’. He was getting back on to his feet, facing in the opposite direction to the now vanished herd, facing me.

At his most dangerous – fresh, massively strong, and with no idea where he was or what to do – he was swinging his great horns back and forth looking for prey and I slammed on the brakes on the cobbled street, thanking God for the grip on my Nike trainers, and went into speedy reverse. Soon there were people between the bull and me and I knew I was safe.  Then he moved in the right direction and a gate was closed behind him to keep the crowd on my part of the course safe. As I walked over to the railings to catch my breath a man was pulled out by paramedics from behind the barrier, blood pumping from his neck.

Then he moved in the right direction and a gate was closed behind him to keep the crowd on my part of the course safe. As I walked over to the railings to catch my breath a man was pulled out by paramedics from behind the barrier, blood pumping from his neck.  (A little later someone pointed out a large bloodstain on my shirt and I can only assume it sprayed out from him.) The wound was evidently bad, but he was holding the bandages to his own throat despite being on a stretcher, so I assumed he was relatively OK. According to the newspapers, after a four-day spell in intensive care he was.

(A little later someone pointed out a large bloodstain on my shirt and I can only assume it sprayed out from him.) The wound was evidently bad, but he was holding the bandages to his own throat despite being on a stretcher, so I assumed he was relatively OK. According to the newspapers, after a four-day spell in intensive care he was.

I walked back to the hotel and called my parents and girlfriend to say I was alive, before heading to a bar where I was told the American runners all met up to confirm the number left standing. It had been a bloody day: two in intensive care, two other serious gorings, a dozen minor injuries from human or bovine feet. As I introduced myself to the men I had seen so calmly warming up before, I discovered that not one of them had been injured, despite having seen them leap in closer to the bulls than anyone else. This may in part be explained by how long they have been running for. One of them, a former English lecturer from New York [Among many other things, Ed.], called Joe Distler, has been running since 1967 and has been the subject of numerous documentaries since. As another of them, a man known as Beef, said to me when I said I didn’t know anyone there.

‘Welcome. These guys are your friends for life.’

We drank from 8.30 a.m. until I fell on to my bed at 4 p.m.

* * *

I took the next day off, letting my torn muscles heal, but decided to run again the day after that, the final day of the feria. This time I took up a position in a doorway halfway along the calle Estafeta. Since most people either like to run on the corners, the beginning, or at the end where they can enter the bullring, I found myself in a relatively clear spot (doubtless helped by few people having the strength to run on the last day). The bulls were Núñez del Cuvillo and this time I got it right, getting into the street and starting jogging about twenty yards ahead of them. [As in the photo. Ed.]

Then, when they cut out the intervening people and reached me, I put on a burst of speed to match that of a bull running at my shoulder, and I did, I achieved templar. In bullfighting, the term means to match the speed of the bull’s charge with the cape, and some say it even means to moderate the charge by doing so. In bull running, it means to match not only your speed but the rhythm of your run to an animal’s.

It was a strangely moving experience running side-by-side with a bull, close enough to touch, although I had been warned that that was frowned upon. His head heaved up and down from the ground as great muscles contracted and relaxed to shift vast weight at a speed equal to my sprint, even though he had already sprinted almost half a mile uphill. He was pure brown in colour and apparently totally ignorant of my existence at his flank, his whole being determined only to keep with his herd and get clear of this mass of humanity. The kinship I felt with him was purely physical, locomotory, experience, but it was still more than superficial.

Later that evening I watched the one and only bullfight I will ever see in Pamplona. The party atmosphere from the streets was magnified in the ring. Not one, but six bands were in operation, each one from a different fan club celebrating. The fans themselves danced and shouted and swore and drank, half the time with their backs to the sand. The matadors valiantly tried to get their attention by fighting, but the bulls were so distracted by the noise – and being run through the streets that morning – that they were almost impossible to make charge. It was an ugly, barbaric thing. And then the bull I had run beside came in, and although he was fought well, he refused to die, despite the sword being within him. As the crowd cheered and booed, swayed and screamed, he walked over to the planks and began a long slow march around the ring, holding on to life as though with some internal clenched fist, refusing to give up, refusing to die. I had run next to this great animal, had matched myself to him as best I could, and in doing so felt some form of connection to the powers that propelled him. Now I watched them all turned inwards in an attempt to defy the tiny, rigid ribbon of steel within his chest, and having been blinded by no beauty, tricked by no displays of courage or prowess by the matadors, I just saw an animal trying to stay on its feet against the insuperable reality of death. I left the plaza de toros with tears in my eyes after that.